The night was clear and the moon was yellow, and the leaves came tumbling down…

911 North Tucker Boulevard

My post today starts with a house – the row house at 911 North Tucker Boulevard, formerly North Twelfth Street. The house was listed for sale in January. It is the last remaining row house on the block, which was once part of a densely-populated neighborhood just north of Downtown. I thought that since this house was the last remaining representative of its kind that there would be a lot of history attached to it, but the only information I could find was from one Post-Dispatch article printed in 1978. In 1978 the house, built in 1857, was sold for the first time in

fifty-five years to St. Louis City Alderman Bruce T. Sommer. Interestingly, Sommer had just been dismissed from his position at St. Louis University Medical School because he disagreed with the school’s redevelopment plans. Sommer bought it from Salvatore “Sam” Domenico who had been living it in since 1923. Domenico bought the house with his wife in 1923, operated a boarding house there, and over a period of five decades watched as all the row houses around his were torn down to accommodate parking lots for Post-Dispatch employees. Directly across the street from the house is the imposing Post-Dispatch building. Before Domenico bought the house, however, the history is less clear.

I searched for information on other addresses on North Twelfth Street to get a better picture of what this neighborhood looked like before 1923. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch archives revealed a neighborhood that once included many townhouses and tenements – home to an interesting collection of characters: German immigrants, working-class newly weds, race track jockeys, vaudeville workers, saloon owners, and a politically-involved class of young African American men – in particular one man named Lee Shelton who resided at 914 North Twelfth Street and who is better known by his nickname: Stacker Lee.

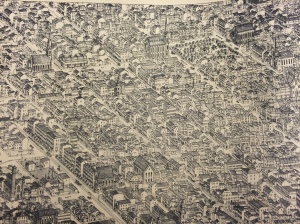

A plate from the 1875 map of St. Louis by Compton and Dry showing the neighborhood that includes 911 and 914 North Twelfth Street

Origins of Stacker Lee

The story of Stacker Lee has taken on the status of legend in American culture. The story was perhaps first told by vaudeville musicians in St. Louis when Stacker Lee was still making headlines. As the story of Stacker Lee made it down the Mississippi, facts became exaggerated, until the man became larger than life. The original nickname Stacker Lee went through several mutations: Stacker Lee, Stackerlee, Stack Lee, Stagger Lee, Stagolee.

Many sources approach the story with a question: did it really happen? Alan Lomax’s The Folk Songs of North America suggests the origins of the story are in Memphis, not St. Louis. Alan Lomax is not even sure whether the actual Stacker Lee was black or white, much less how exactly he got his infamous nickname. The only part of the story that nobody seems to contest was that Stacker Lee was a bad man, but was he really?

Stacker Lee Shot Billy

The facts of the story are not up for debate: Lee Shelton, nicknamed Stacker Lee, shot William (Billy) Lyons on Christmas night, 1895 in a saloon at 1101 Morgan Street in St. Louis. The wound to Lyons’ abdomen was not immediately fatal, but he died that night in the City Hospital. Shelton fled the scene but was soon arrested. There were dozens of witnesses. Shelton soon found himself serving a 25 year prison sentence for murder at the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City. He was released on Thanksgiving twelve years later by Governor Herbert Hadley, but within two years he was back in prison for robbery. He died from tuberculosis on March 11, 1912 while still in prison. He is buried in North City.

Entry for William Lyons on December 25, 1895 in the St. Louis City Record of Deaths. Cause of death is written as “Gunshotwound of Abdomen. Homicide.”

Stacker Lee: The Legend and the Man

In the stories about Stacker Lee, he is portrayed as the ultimate bad man, a man concerned only with his own survival – a man with no morals. He lacks empathy and shows no remorse, even after shooting a man dead. The stories say that Stacker Lee “ran the town” and that he was so intimidating that he was given a second trial because the judge was afraid to convict him. Some versions of the story say that Stacker Lee was more evil than the Devil himself. Songs about Stacker Lee have poor Billy Lyons begging for his life when accosted by the terrible Stacker Lee. But what evidence is there to support any of these claims?

We do know some details about what happened that night. First of all, Billy and Stacker Lee were not strangers – they were friends. But, according to one source, they had different political associations. In a 1911 Post-Dispatch article, Stacker Lee was described as a “negro politician” and former head of an African American political club. Stacker Lee was loyal to the Democratic Party, which at the time was extremely unpopular among African Americans. The Globe-Democrat described Billy as a twenty-five-year-old (though the official record of deaths for St. Louis says Billy was 31) levee hand and Stacker Lee as a carriage driver.

At the time saloons were popular meeting places for local political organizations, especially the saloon where Lee and Billy met that Christmas night “in exuberant spirits.” The crucial detail of the story is that Lee and Billy get into an argument about politics which concludes with Billy taking Lee’s hat and refusing to give it back. So Lee shoots Billy. The stories all assert that Lee shot Billy because he was a bad bad guy, but another possibility occurred to me: Lee was very drunk.

Think about it: two men, very drunk on Christmas night, get into a heated political discussion, and one shoots the other. Lee was drunk – his prefrontal cortex impaired – so instead of walking away or even fighting, he decides to just pull the trigger.

I am not saying that Lee was blameless, but this murder (probably while intoxicated) itself hardly draws the picture of a ruthless killer. The facts suggest a young man, politically involved, who did one very bad thing and paid the price. Even the later robbery, during which Lee broke another black man’s skull with a revolver, is to some extent explainable in terms of Lee’s post-prison desperation. But the stories that have sprung up around his name have different interpretations of events.

Folklorist B. A. Botkin has recorded his version of the story: Stacker Lee was born on Market Street and lived there even as an adult. Market Street was historically part of an important African American neighborhood, which was demolished in the 1950s. His friends gave him the name of Stacker Lee because he worked on a steamboat named the Stacker Lee as a stoker. He had a collection of hats at his Market Street home, and in a deal with the Devil, he sold his soul so that one of his hats could be charmed to protect him. Stacker Lee loved to gamble. One night he is so caught up with his own luck that he forgets about his hat, hung on the back of his chair. The Devil, disguised as Billy Lyons takes the magical hat and Stacker Lee chases him. Lee finds the real Billy and shoots him, despite Billy’s friends assuring Lee that Billy was innocent. Stacker Lee is soon taken to jail and sentenced to 75 years in prison.

Even though it is clear that Botkin’s version of the story is highly fictionalized, it is this take on the story that has kept memory of Lee alive in the American consciousness.

Stacker Lee’s Legacy

Musicians have been writing songs about Stacker Lee for over a hundred years now. By the start of the twentieth century, fifteen years after Lee pulled the trigger, vaudeville musicians were singing tunes about Stack Lee and Billy. By the 1920s songs about Stacker Lee had entered into the mainstream of American culture. Lloyd Price’s 1958 version rose to the top of the charts in the US and the UK. Versions of the song have been recorded by Tina Turner, James Brown, Pat Boone, the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, Beck, the Black Keys, and even Samuel L. Jackson for the movie Black Snake Moan. In all, some two-hundred songs have been recorded about Stacker Lee.

The story of Stacker Lee is still inspiring creative work. A well researched graphic novel by Derek McCulloch and Shepherd Hendrix titled Stagger Lee was published in 2006. Douglas Kearney’s 2013 poem, “The Labor of Stagger Lee: Boar,” describes Lee as someone who “live by the want and die by the noose.”

But his legacy in song and poetry begs the question, why? Why has this story stayed alive through song? What is special about this murder? After all, in St. Louis that Christmas night, there were six other murders. In a 1979 Post-Dispatch piece, Elaine Viets theorizes that Lee’s story quickly took on symbolic meaning for the struggle urban African Americans faced in the late 19th and early 20th century – “he was a mean man in a hard world.” He was a man who lived at 914 North Twelfth Street.

Lloyd Price’s “Stagger Lee”

Very interesting. I think you should write some stories about St. Charles too. The book of St. Charles Ghosts has me wanting to go ghost hunting on Main St.

LikeLiked by 1 person

New information about 911 Tucker can be found at http://developstl.org/911-n-tucker-blvd-saint-louis-mo-63101

LikeLike

I finished using music to carry forward the spirit of freedom. It is the first time I see this song and just like most American songs, it reflects a rich sense of the times.

LikeLike